Stereotypes vs Optimistic Aging in America

Growing old with Attitude

Unofficially, when we reach the age of about 60, we enter a new stage of life - complete with its own set of assumptions. They involve an individual's attitude about aging and also public perception – and it's this dynamic that requires attention if we want to successfully navigate our elder years on our own terms.

When I was in my early 60s, I attended a 'Mini Med School' at the University of California, Davis, for a series of lectures covering issues that people may encounter throughout the aging process. I paid particular attention to presentations that dealt with the societal aspects of growing old and subsequently dove into the topic – to, quite honestly, be surprised and dismayed. After all, public perception not only affects our self-esteem as individuals, it can literally impact our health and longevity.

As I grew older, (I'm now 76), I noticed behaviors changing toward me. Examples include increasingly being addressed as 'Dear, Sweetie, and Hon' by cashiers (Starbucks was a prime source) and asked if I wanted the senior discount. All this based solely on the young person's assessment of my physical self. I didn't suffer this (perceived) insult quietly. I left a piece of my mind with most of the well-intended offenders, and I still have pieces left to hand out.

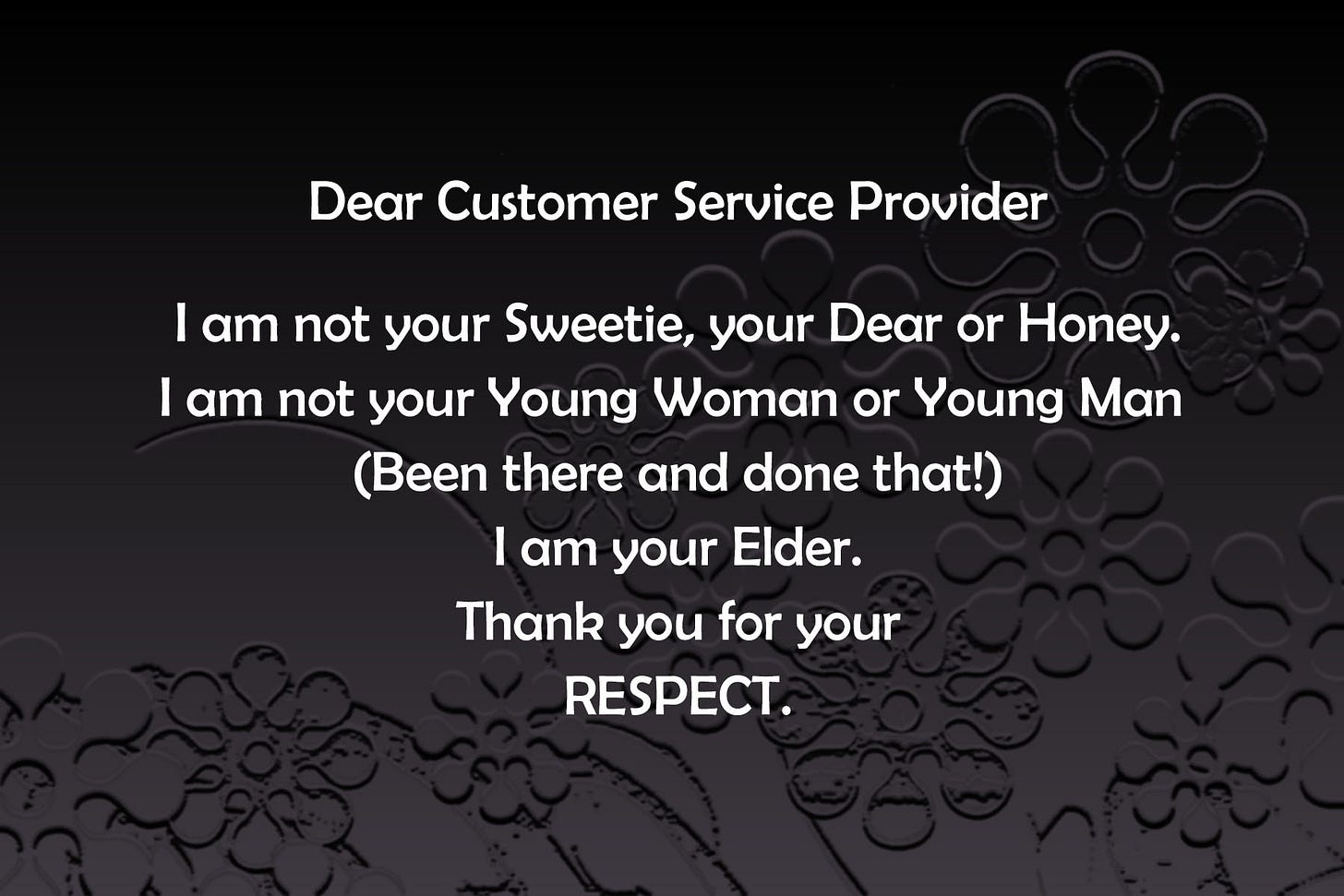

My negative reaction was not due to my own feelings about what it means to grow old – but because the servers, ticket takers, and cashiers made a judgment about me based solely on the young person’s assessment of my physical appearance – and, from there, addressed me as if I was somehow diminished - at which point I presented many of them with the card pictured above. Those of you over the age of 65 will likely know what I'm talking about.

Now, after years of making optimistic and healthy aging a personal and professional goal, I'm encouraged by the increased interest in a topic that will eventually be important to everyone fortunate enough to experience a long life. But I'm also very concerned about the barriers we continue to face. Here's a bit of history:

In the pre-industrial world, elders held the keys to the family kingdom. They owned the land and home and were the source of livelihood for the entire family which often included several generations. Trades, wealth, land, and futures were a legacy handed down and valued. The elder in the family retained a position of respected authority – the keeper of family memories, traditions, and culture. Once that traditional family base was disrupted by the Industrial Revolution offering financial opportunity outside the nuclear family, the dynamic changed. Of course, much of that was beneficial for people and built our modern economies. But at the same time, the hierarchal structure of the family dramatically changed. The overall status of elders declined, and, in America, older people became increasingly irrelevant as contributors to society.

Today the dominant perception of elders (mostly in western cultures) is associated with decline, dependence, and disability. It's apparent in American healthcare, media, institutions, politics, and government – among other aspects of life. But there is a counter to all these perceptions – and it's called reality. A majority of Americans over 60 are well, active, and contributing to society.

Becca Levy, Ph.D., offers statistics and science-based observations about aging in "Breaking the Age Code," – a book I've read twice (so far). If the many benefits of positive aging could overcome popular perceptions, life would be richer for us all – despite our age. It's hard to overcome messages we get from our youth-oriented culture – birthday cards joking about "It's all downhill" and media that idolizes youth and supports stereotypes of aging – slow, forgetful, broken, on-the-way-out, a burden. Levy says the truth is very different - that the aging brain develops profound abilities and offers resources not onboard in our younger years. Furthermore, Levy (and others) say that when we adopt positive beliefs about aging, both brain and body benefit. Scores of academic studies cite evidence that state-of-mind impacts the development of brain health and physical functioning over time. Positive attitude fosters physical and mental health at any age and is particularly evident in older people.

I won't go so far as to suggest 'ageism' is a social conspiracy. But the stereotype of aging as a decent into irrelevance and disability is supported and fostered in so many aspects of American life that it's no wonder the dangers and downsides of aging persist. And they affect nearly every aspect of older life. For example: It's not okay to make racial jokes, but jokes about elders are game; the film industry seldom features older actors in positive roles (peculiar or pitiful? Yes!); medical caregivers accept decline as inevitable in older patients – untreatable - as though age is a disease). And don't get me started on the cosmetic industry and its loaded messages to women.

There is general agreement within the community of researchers and scientists that this negative approach about growing old in America directly impacts the quality of our later years. It's no wonder so many people accept these common stereotypes coming from multiple sources.

At the same time, science is busy discovering what drives some of the infirmities of older age and how to manage or eliminate them. This is very relevant as current research indicates that an optimal (and reachable) lifespan may be about 125 years! Other studies offer evidence that belies the negative assumptions about the aging experience – with attributes such as greater wisdom, calm, self-confidence, deeper relationships, and self-respect that come with age. However, these positive details are often buried in specialized sources that don't reach the general public. Levy's book and others like it have little chance of making noise above the continuous reinforcement of stereotypes about aging.

I think my attitude about valuing elders was formed by living with my grandparents for 17 years. They were my authority figures throughout childhood, and I never questioned their stature. Didn't think of them as 'old' or incapable. I loved hearing stories about their own childhoods (one born in the Black Country of England and the other to Polish immigrants on a simple farm in the midwest). Their influence made it natural for me to later work in a convalescent home and appreciate the company of elders living out the last days of their lives. They were some of the most interesting people I met while working through college. I still remember their stories.

Now a card-carrying member of the elder generation, I'd like to help set the record straight. Advancing age is not to be feared but is an opportunity to build on a lifetime of earned experience. A time to appreciate the unique gifts we bring to the lives of people around us. A call to take charge of both our physical and our mental health. To do these things, it's critical we reject the stereotypes that stalk us. Take pride in earning the status of an Elder (not elderly, a descriptive label loaded with negatives).

Whatever your age, I hope you'll take a look at your own assumptions about what it means to grow old. There's plenty of affirmative information on the beatitudes of advanced age, though you won't find it in mainstream media. It's worth the effort to do some online research. Here are a few suggestions:

Episode 44: What science tells us about living longer

Nat Geo - The secrets to a long life -- monographs on world’s oldest people

Breaking the Age Code, by Becca Levy

How you feel about aging could affect health. Here's how to keep the right attitude.

Aging Positively: Psychology's Connection to Aging

***

Thanks for your attention - I value your time and your input. If you have suggestions or reflections, please send me your thoughts at darby@darbypatterson.com. And feel free to copy my calling card above in case you want to make your position clear!

Also, take advantage of a chance to grab some Free eBooks - cozy mysteries (Including mine - The Song of Jackass Creek - great reviews on Amazon! )